Il Profumo: Cultura, storia e tecniche

Perfume: Culture, History, and Techniques

Lorenzo Villoresi (b. 1956) is known all over the world for his prestigious custom-made fragrances. This self-trained perfumer from Florence studied Ancient history, philosophy, and religion, and travelled extensively through Northern Africa and the Middle-East before committing himself to the world of perfumery and fragrant raw materials. The following is a synopsis of his first book, the title of which translates as "Perfume: Culture, History, and Techniques". The book contains descriptions of perfumery techniques, an overview of raw materials and essences, separate chapters on the history of perfume and famous perfume quotes in literature, a special section dedicated to aromatherapy, and an extensive glossary. A concise abstract of this excellent reference book would be forcefully over-simplifying; therefore this synopsis revolves around a selection of Villoresi’s personal accounts and views on perfumery. Although these biographical snippets play a marginal role in the book, their reconstruction will contribute to a better understanding of the concepts and ideas behind Villoresi’s fragrant creations.

The smell of diffidence

According to Franco Cardini, professor of Medieval History at the University of Florence, Western culture of smell is characterized by an interesting historical ambiguity. On the one hand it is rooted in the traditions of Ancient Greece and Rome, where aromas and essences were associated with feminine frailty and the dangerous world of magic. Although the hedonistic use of fragrant oils and balms was widespread among Greeks and Romans alike, they generally regarded it as unworthy of serious consideration. The development of perfume remained largely confined to its Arab and Persian origins, cultures of which they were highly diffident. A contrasting tendency emerged in the Hellenic (and later Christian) tradition, which opened the path to Oriental cultures – initially through the expansion of Alexander the Great’s empire, later through the dispersion of the Christian Bible. Trading relationships and cultural exchanges with Middle Eastern cultures progressively intensified, and new spice routes became the object of crusades and wars in the Middle Ages.

Despite these cross-cultural influences, the sense of smell continues to evoque suspicion in our contemporary Western habits and behaviour. There seems to be a platonic hierarchy in our culture that places our senses of sight and hearing in the realm of spiritual refinement – music, poetry, painting and sculpture representing all things civilised – whereas the senses of smell, taste, and touch are primarily linked to lower elements of culture, such as food and eroticism, which have been traditionally perceived as conveyers of spiritual corruption. Western perfumery as we know it today is a product of this cultural heritage; perhaps it is within this critical perspective, that Lorenzo Villoresi’s refreshing outlook on perfumery is best explained.

Lorenzo... of Arabia

Lorenzo Villoresi was never keen on the sterile atmosphere, and the highly commercialized aesthetics of perfume shops in his native city. Raised between the opulence of his family’s magnificent palazzo in the historical heart of Florence and their villa in the Tuscan countryside, Lorenzo discovered a strong connection with the rural, outdoor life at a young age. His father Luigi taught him to appreciate the beauty and therapeutical qualities of various botanical species in their gardens, and showed him the relationship between Nature and the world of art and literature. Then came his love for the Arab world: his mother Clarissa had opened a small boutique in Cairo after World War II, where she sold artisanal products from Florence. During his adolescence, Lorenzo was intrigued by his mother’s recollections of Egypt, a fascination that was to become a crucial element in his life. As he prepared his academic thesis on the role of death in ancient Judaic and Hellenic traditions, he started a cosmopolitan life which would constantly draw him back to Northern Africa and the Middle East. He followed the traces of Hebrew, Egyptian and Mesopotamic cultures by making long, distant travels, often without any specific goal. Moving from the big bazaars in the Egyptian capital to the market places of Jerusalem, travelling through desolate places in the Sinaï mountains, Lorenzo discovered a world historically linked to his own culture, but with a very distinct outlook on life. It was in the Middle East, the cradle of the culture of fragrances, that his love for essences and perfumes was shaped – and it was here that his desire to reinstall the old, faded tradition of Florentine perfumery was nurtured.

From Northern Africa to the far Orient, Lorenzo noticed how people display an openness and ease towards scents unparallelled in the West. His first overseas contact with the culture of perfume took place in Cairo, in 1981, where he was approached on the streets by an individual who invited him to his perfume shop. It was nothing like the cold, depersonalized boutiques in Western countries: the atmosphere was pleasant, inviting, and calm, and the natural hospitality of the people in the shop made him instantly feel at ease. No trace of large, shiny perfume bottles either; instead, small containers filled with essential oils, and great varieties of fresh spices stored in bags and jars. Products that Lorenzo would, from then on, regularly bring back to his family and friends in Italy. It was in those little perfume shops that he observed the trading game in the Arab world, noticing the extensive time and attention that hosts take for their guests – a quality largely underestimated in the West.

First steps

Lorenzo travelled back and forth between his native Italy and the Middle East until 1989; meanwhile, his collection of oriental spices and fragrant containers grew rapidly. He avidly read old books on distillation techniques and enfleurage, and studied the history of perfumery and botany. He enjoyed blending fragrant oils and creating potpourris for relatives and friends; they were simple fragrances at first, but Lorenzo gradually started experimenting with various production techniques. Inventor Vittorio Orioli and industrialist Ludovico Martelli (whose father was a perfumer) helped him find the proper resources and materials; Vittorio also introduced him to Dr. Sandro Meucci, who taught him valuable lessons in chemistry.

In 1990 he was approached by a friend, Maria Grazia, who worked for Fendi in Rome; she knew about his passion for fragrances, and recognized his talent for fragrant creations. She commissioned various potpourris for the Fendi sisters, and it proved to be a success: in that same year he opened his own artisanal house – much to the amazement of his acquaintances, who knew him as a serious academic. His friend Enrico Minio, nephew of the famous tailor Roberto Capucci, played a key role in the setup of his business: together they developed, among many things, the idea of creating a line of fragrant oils. The Oriental culture would remain a major source of inspiration in Villoresi’s work.

Creating a perfume

The modern media often depict an image of perfumery that is superficial, narcissistic and extrovert; it is a completely distorted reflection of the hard work and serious dedication that perfumers invest in their creations. Perfumery differs greatly from other crafts, in that our olfactory perception is instantaneous and short-lived: as memory and concentration play a vital role in the creative process, solitude and tranquility are essential working conditions to a perfumer.

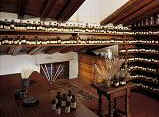

For Villoresi, the start of a new creation is always preceded by an (indefinite) image in his mind. He selects essences from his perfume organ, lays them out in front of him, and then starts grouping them: all the woody notes on one side, the green ones in another group, and so on. It is an orchestra of fragrances, where all instruments have their distinct sound, and each one needs to be in tune with the rest. Lorenzo faces the bottles in the line-up, evaluates their different characteristics, pulls some of them towards him, while pushing back others. Each group needs a calm, careful evaluation; before altering one, it is sometimes preferable to wait a few days in order to "refresh" the nose. After the definitive group arrangements, each one is blended separately. Proportions and quantities are meticulously registered, as they cannot be reproduced by approximation. Since reactions between ingredients are never entirely predictable (and mistakes are usually irreversable) it takes many months before a group is perfectly tuned. Next, the various groups need to be blended together; once the composition is stabilized, it is diluted in alcohol. The final perfume is then selected from many trial versions.

Perfume ingredients

Although Villoresi has a very large collection of essences at his disposal, he is constantly on the outlook for new ingredients, and loves to experiment with distillation techniques. As often as possible, he sets out to explore the use of natural raw materials: for instance, shortly before Il Profumo was written, he had ordered a Mexican herb called mate from which he created a tincture, being curious about its effect in fragrant creations. Around the same time, he was considering distilling a powder obtained from cypress wood, which in his mind would result in a woody note with a resinous and aromatic twist: he estimated that it would be a nice base note for a new fragrance for men. Despite having a preference for natural ingredients (which often give a nice roundness to a fragrance), Villoresi underlines the importance of synthetics in modern perfumery as well. Many softening, harmonizing, or blurring effects would not be technically achievable without the use of synthetic ingredients; and even when a natural raw material is available, its extract can be of modest quality or intensity (such is the case of the gardenia, for example) while being extremely expensive to produce. Villoresi therefore rejects the common view that synthetic ingredients are simply "cheap" or "fake" alternatives to natural ingredients.

Custom-made perfumes

Besides a highly acclaimed collection of commercially available, ready-made perfumes, Villoresi offers the possibility to create perfectly exclusive, personalized scents. Clients interested in a custom-made perfume are invited by appointment to Villoresi’s studio in the Via de’ Bardi in Florence; in the space of two or three hours, they express their thoughts and ideas about their envisaged fragrance. A consultation usually starts with a discussion about essences in general, often with references to other perfumes as well; the focus then shifts to the client’s true olfactory preferences. When a perfume is to reflect the client’s personality, a good dosis of introspection is required: Villoresi underlines that he is not a clairvoyant, and that he sees his role in this process as that of an interpreter, a mere mediator between the client and the final product. The client should therefore have a vision of their own, and feel comfortable enough to share all their thoughts during the consultation. In some cases, a second appointment is made to work out details or to tweak the composition.

Contrary to what one might expect from such an exclusive approach, Villoresi’s clients are from all ages, and all walks of life. His studio may be frequently visited by famous people and colleagues (among which Jean Laporte of Maître Parfumeur et Gantier, Olivier Creed, the late Annick Goutal, or renowed perfumers such as Guy Robert), but his services are accessible to anyone with a true passion for perfume. The price of a custom-made perfume depends on the length of the consultation, the cost of ingredients (a rather important variable), the choice for a specific bottle, and the request of accessories (such as a casing); the approximate cost of a session is between 600 and 750 Euros. The end result is a unique fragrance, of which the recipe, its description, and a list of the owner’s personal tastes are carefully archived in Lorenzo’s studio in Florence. Clients usually purchase 100mL (3,4 Fl.oz.) of their personalized perfume, which can be easily recreated on their specific demand; it is also possible to order other products in the same personalized fragrance (such as body lotion, bath oil, body oil, etc).

Within less than a decade, Lorenzo Villoresi established a worldwide reputation through his distinguished outlook on perfumery, and his phenomenal craftsmanship. Il Profumo was published only five years after he opened the doors of his business in Florence, and yet by that time he had already created over 400 personalized fragrances, and gained a large following of perfume connoisseurs. Nevertheless, even Lorenzo cannot deny that some clients are harder to please than others. With much love, he recalls the first time he composed a perfume for his mother, who asked him to make a jasmin-based scent. He used a selection of pure and natural jasmin essences, creating a fragrance that she was very fond of. Each time she finished a bottle, he would prepare her a new one according to the same formula – and each time, she was convinced it was not the same as the previous one. He would then explain that it was because the new fragrance was still fresh, and that it would gradually mature, developing different nuances. "But I ended up never being believed. Mothers are very difficult clients!"

Villoresi's publications linked to perfumery:

Il Profumo: Cultura, storia e tecniche. Firenze: Ponte alle Grazie (1995)L'Arte del Bagno. Firenze: Ponte alle Grazie (1995)

Il Mondo del Profumo (editor). Milano: RCS Libri & Grandi Opere (1996/1997)

Thanks to Grant Osborne (Basenotes.net) and Lorenzo Villoresi for their kind help with this article.

This article was originally published on www.basenotes.net.